Amazon is the biggest E-commerce website on earth. But when it comes to its visibility on Google, how big is it?

Some weeks ago, Amazon decided to slash its affiliate rates. It surely wasn’t the best timing for a lot of small companies or individuals earning a living with these websites, but it is not one of the criteria Amazon uses when it has to make a move, let’s be honest.

First of all, a bit of reminder for those of you who don’t know it yet. I will quote the definition I included in another post: Affiliate websites are one of the most simple and wide-spreaded business model on the internet. The process consists in building a website to rank on commercial keywords (like “best shoes for running”), and link to E-commerce websites (like Amazon) in your content to get a cut on products bought by your users.

For quite some time, Amazon had one of the most popular affiliate programs out there because its rates were higher than most of its competitors. So why would they reduce them so much?

One guess is that Amazon is now on a monopoly-like situation in a lot of countries when it comes to E-commerce. A similar situation Google has on the search engine market. Its organic visibility is high on commercial keywords and a lot of affiliate websites are ranking as well: why would the company pay a high percentage to affiliates if customers are very likely to buy from the brand anyway? That is what Fran Murillo shared in this tweet (in Spanish but really worth translating).

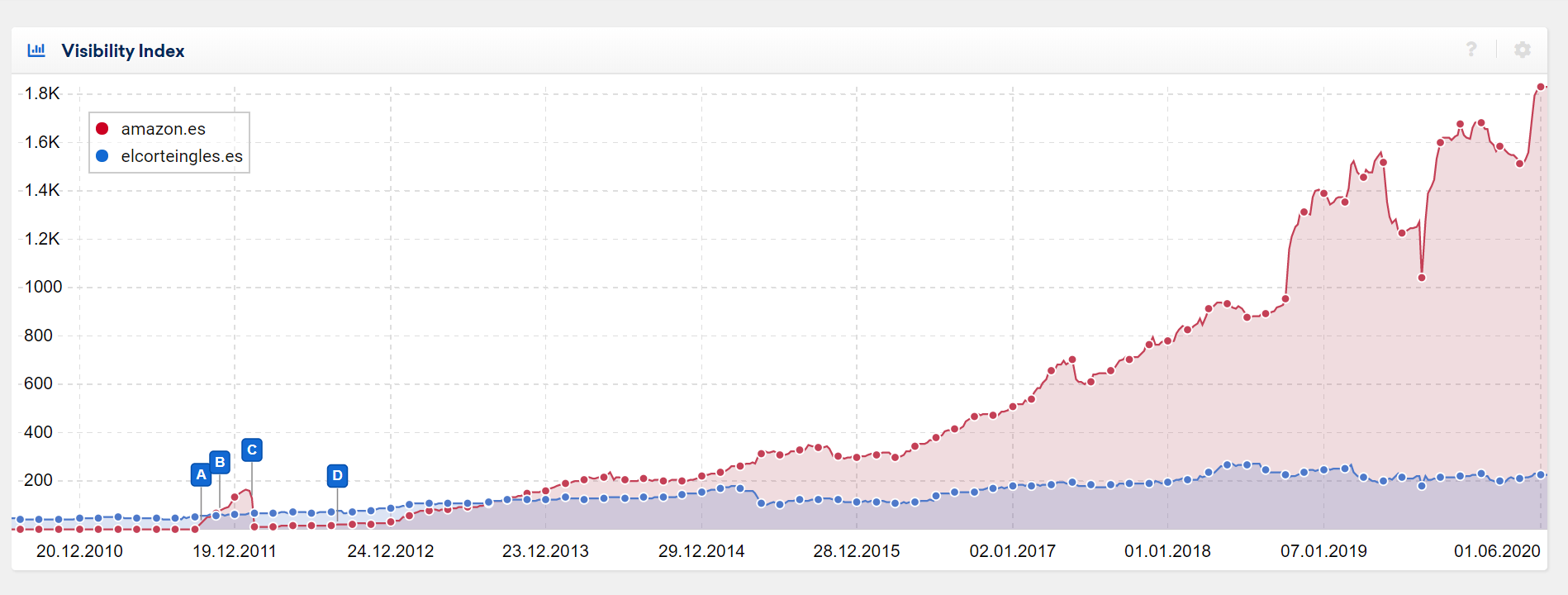

And when you look at the visibility Amazon has on this market and you compare it with the closest competitor (El Corte Inglés), you can indeed see an impressive – and growing – difference.

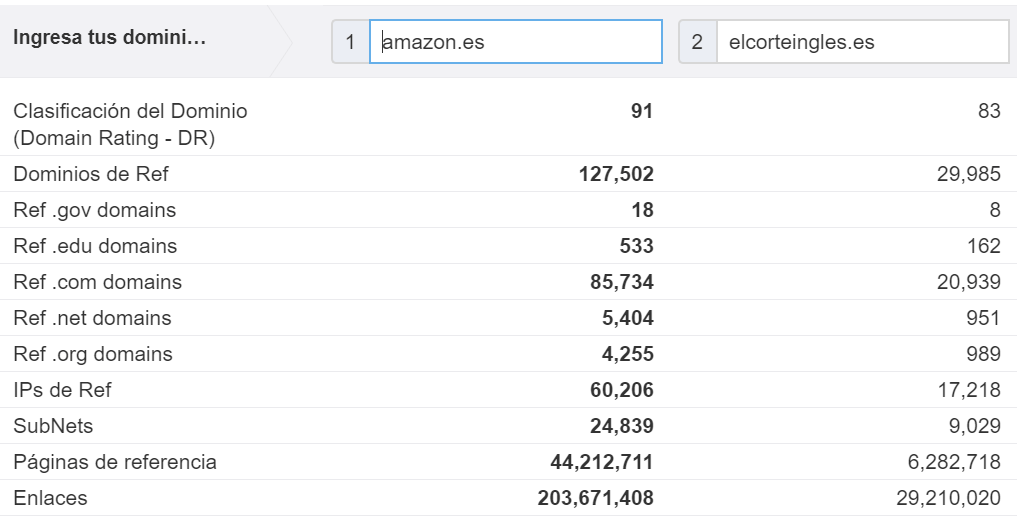

The same comment applies for metrics available in Ahrefs:

I have a strong feeling (as a lot of people) that the affiliate rates were slashed just because Amazon don’t need them anymore. Indeed, they are often better ranked than them and customers often start to look for a product on Amazon. This is exactly why branded keywords linked to a product (like “meat grinder amazon”) are actually on the rise if you look at the data available in the Keyword Planner or any SEO tool.

It sounds kind of logical, but what about trying to validate these assumptions based on real data? That is exactly what I did !

Methodology (TL;DR)

For the full methodology, please refer to the end of the article where I explain everything more in-depth.

Summary:

- The study was done for the Spanish market only

- The study includes 14.168 transactional keywords, with at least 1.000 searches per month

- I extracted Google’s first page results (usually between 7 & 10) for all of these queries, using a regular Desktop User-Agent

- I then crawled all theses results (around 90.000 individuals URLs) to detect websites with a link to Amazon. If a link was found, I assumed this website was an Amazon’s affiliate.

The last point is a strong assumption but there actually very few websites linking out to Amazon without being an affiliate. The error margin is pretty low here.

Common “issues” with Amazon SEO

It’s no secret that Amazon is doing very well on transactional queries on Google. I mean, it is one of the biggest E-commerce worldwide and it actually makes sense that Google includes it for a lot of queries.

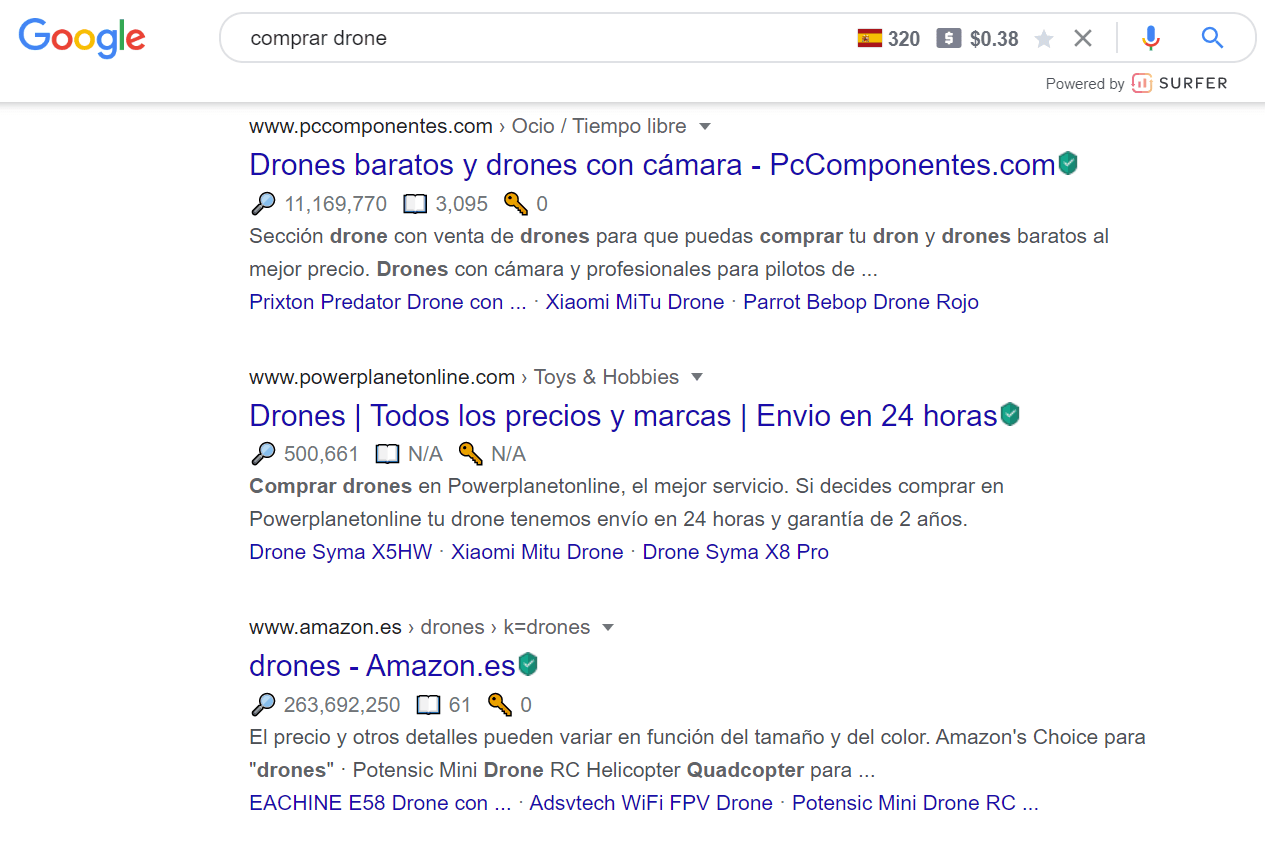

Nevertheless, you often have ludicrous situations that can create frustration for other E-commerce owners. The first and most frequent is when Amazon is doing so well on queries with a simple internal search URL, like the example below.

And I can now ensure that this is not an isolated case. Out of the 18479 unique URLs from Amazon I detected for all the queries I analyzed, 52% were search results URLs.

I’ve never seen such importance for search result pages and I perfectly know why: internal search pages are usually blocked or noindexed by the SEO team.

This article quite explains why: to avoid Google spending time crawling useless pages and to provide a good UX. But it also explains that there are cases where you want to index them, and Amazon clearly went this way and it worked pretty well for them. It is simply easier to scale search pages than include them in your architecture.

I cannot blame Google for ranking them because to be honest, there is often no practical differences between a category page and a search page for most E-commerce websites. You have a list of products and a set of filters you can use.

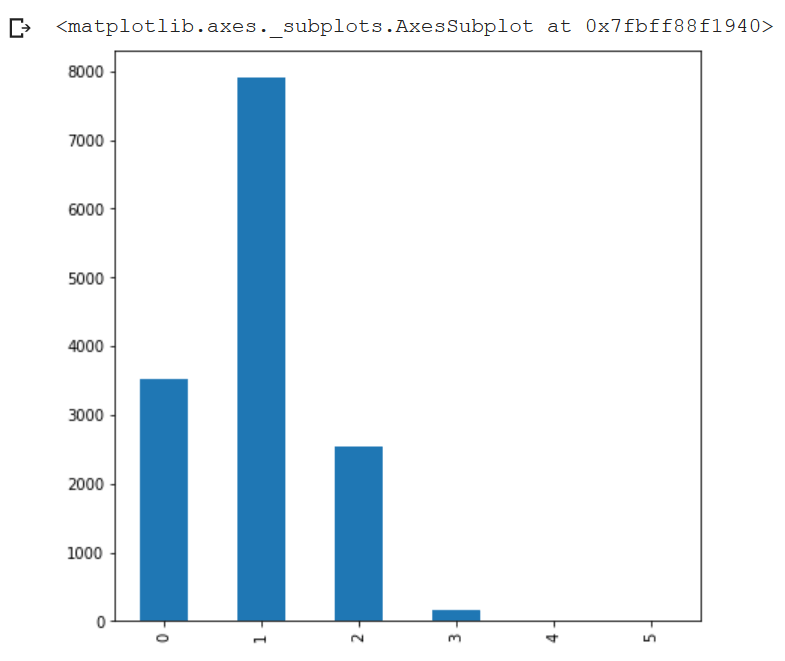

We then have situations where you have more than one Amazon results. In my dataset, I actually calculated the number of Amazon results per query and I ended up with the following frequency graph, which means that Amazon manages to rank more than one result in a lot of cases.

I don’t really know how to defend a lot of them, mainly for two reasons:

- Google claimed that it wanted to include more diversity on its SERPs and you have yet too many results where this is not the case

- You could argue that “yeah, but what if Google has no other relevant domain to show”. I can buy that for some queries, but not the majority like the query “touch screen watch” where Amazon gets the first 3 organic spots:

What is Amazon’s own organic visibility?

Based on the data I extracted from our 14.168 queries, I detected that around 11% of all organic results in the first page were from Amazon. Maybe not the impressive number you were expecting, but note that the closest competitor, El Corte Inglés, is only at 4%.

Please note that this percentage was obtained adding results where amazon.es appeared (10.6%) but also amazon.com (0.4%), that can ranked in some cases.

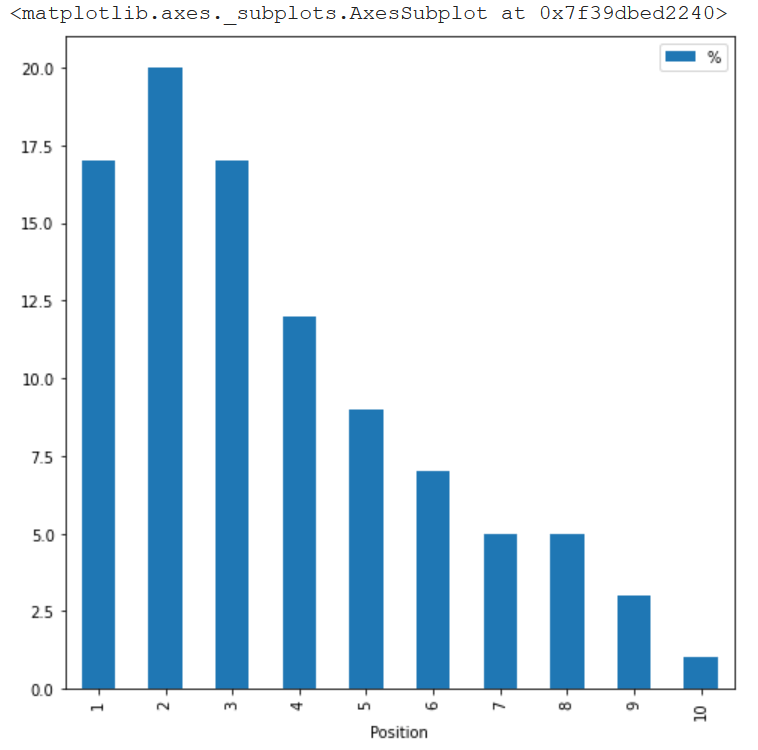

Moreover, if I extract the exact same number, but per position, you realize that Amazon’s results are very concentrated within the first positions. What does it mean? That even if Amazon has 11% of the total results, the traffic share it gets is higher because the first 3 results usually get between 50 and 80 percent of the clicks (it depends on the industry and the device).

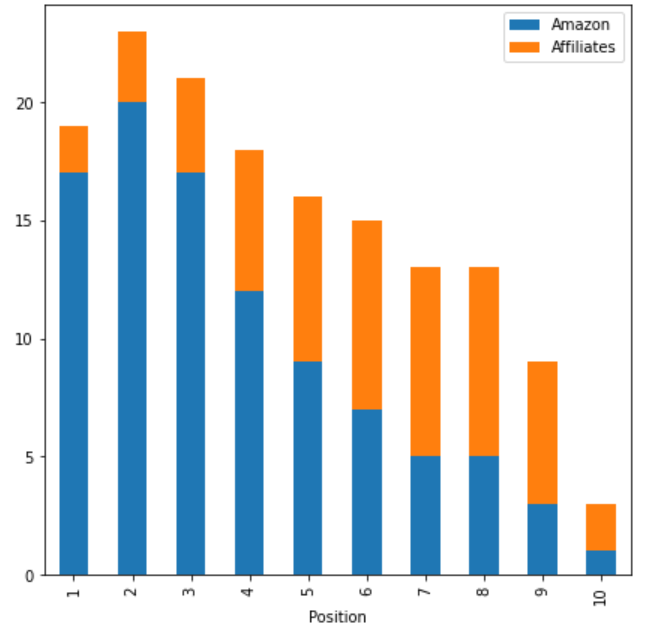

This is great, but what we actually want to figure now, it the real visibility Amazon has, with its own websites but also with its affiliate network. Will it make a great difference?

What is Amazon’s real online visibility?

As I explained at the beginning, if a website had a link to any Amazon’s website or amzn.to (widely used to shorten its URLs), I assumed the website was an affiliate.

If we add affiliates in the previous graph, we end up having not 11% but 16% of the total organic results being from Amazon or Amazon affiliates.

Regarding repartition, affiliate are usually located lower than Amazon on Google:

What can we conclude with these data?

In plain English, the data shows that, within our set of 14.168 keywords, the same website (or a website promoting it) will almost appear one out of 5 times, for the 4 first spots.

This is actually huge, because more than 50% product searches start on Amazon. If you then add the share of traffic from Google going to Amazon, we would end up with something like a 70% real market share. If this is not a monopoly, I don’t know what would be.

To current affiliates: be aware that even if Amazon is still profitable for a lot of you, I don’t think they will increase their rates ever again. A part of its current success was achieved thanks to the synergy that existed during years between you and them: you provided the links & the traffic in exchange of a commission on sales. If you think you can manage an E-commerce, go for it because your will be less dependent on an external factor to ensure the sustainability of your business.

To Amazon’s competitors: there is a real opportunity to boost your affiliate game and try to get a piece of the market share indicated in orange in my previous graph.

I hope you liked the study and I’ll be very happy to read your opinion or feedback in the comment section. If you are interested and as mentioned in the introduction, the full methodology is explained below.

Full Methodology

If you are here, your are interested in the full methodology. I will try to explain it in-depth, including part of Python code I used to manipulate everything. Any issue that is spotted in the methodology or in the process, feel free to let me know.

Keyword Selection

The list was obtained following these steps:

- Extract the keyword list from amazon.es in SEMRUSH. I don’t think that my data are Amazon-oriented by doing that because there are actually very few commercial keywords where Amazon won’t be ranked within the first 100 results. It is a good way to get an extensive list of commercial keywords.

- To be sure to exclude most non-commercial keywords, I filter the keyword list to include only keywords where the “Shopping” module would be present.

- I then exclude most branded keywords using the Exclude filter from SEMRUSH

- And I finally filtered out all keywords with less than 1.000 searches per month. I did this part to end up with a manageable set of keywords, not a list of 100.000 keywords. I don’t have the infrastructure to run a study on such a dataset.

Scrape Google’s SERPs

I followed what Carlos explains in this post (in Spanish), adding only a custom extraction to extract results’ URLs. The only important thing here was to lower the speed to avoid Google from blocking my crawl. I did it at 0.1 URL/s. So yes, the crawl lasted almost for 2 days.

I know that there are more efficient way to do that (using proxy or APIs), but I didn’t want to spend money on that study to be honest.

Crawl Results

Based on the first crawl, I created a list of unique URLs extracted by Screaming Frog. The code was the following:

#Load Pandas

import pandas as pd

#Load the export from Screaming Frog

x = pd.read_csv('list_mode_export.csv')

#Create an empty Series

concat = pd.Series()

#Loop all columns containing URLs we want to crawl

for i in range(1,11):

concat = pd.concat([concat,x['Links {}'.format(i)]])

#Remove empty rows because some queries have less than 10 results

concat = concat.dropna()

#Not mandatory because Screaming Frog does that anyway

concat = concat.drop_duplicates()

#Create the CSV we will feed to Screaming Frog

concat.to_csv('list.csv')

The second crawl included 90.215 unique URLs. I didn’t limit the speed here and I was blocked by several websites. But I reviewed them all and none of them were affiliates, so it didn’t impact my analysis.

I configured Screaming Frog to extract nothing but external links, which is really what matters here. It allowed me to speed up the process because my computer is not very powerful.

Crawl analysis

Here are the pieces of code used to get all the information mentioned in this article. I tried to comment it to make it clear and explain the logic if you don’t know how to read Python code. Should you have any doubt, please let me know and I’ll be happy to explain it to you.

Initial load

#Import Pandas

import pandas as pd

#Import Matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#Import Numpy

import numpy as np

#Load data from the first crawl

data = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/My Drive/Perso/list_mode_export.csv')

#Keep useful columns

data = data[[

'Address',

'Links 1',

'Links 2',

'Links 3',

'Links 4',

'Links 5',

'Links 6',

'Links 7',

'Links 8',

'Links 9',

'Links 10'

]]

#Retrieve the keyword from the Google's URL and set it as index

data['Keyword'] = data['Address'].str.extract('q=(.*)&rls')

data['Keyword'] = data['Keyword'].str.replace('+',' ')

#Just in case

data = data.drop_duplicates()

data = data.set_index('Keyword')

#Load data from the second crawl

outlinks = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/My Drive/Perso/all_outlinks.csv')

#Keep AHREF Link only

outlinks = outlinks[outlinks['Type']=='AHREF']

#Remove Amazon's websites

outlinks = outlinks[outlinks['Source'].str.contains('https://www.amazon')==False]

#Extract destination domain

outlinks['Domain'] = outlinks['Destination'].str.extract('^(?:https?:\/\/)?(?:[^@\/\n]+@)?(?:www\.)?([^:\/?\n]+)')

#Keep URLs with a link to Amazon

outlinks = outlinks[(outlinks['Domain']=='amazon.es')|(outlinks['Domain']=='amazon.com')|(outlinks['Domain']=='amzn.to')]

Frequency table of number of Amazon’s results per query

def number_amazon_results(df):

df['Number_amazon_results'] = np.sum(df.str.contains('https://www.amazon'))

return df

#Apply the function

data = data.apply(number_amazon_results, axis = 1)

data['Number_amazon_results'].value_counts().sort_index()

Number of search results from Amazon

def number_amazon_search_results(df):

df['Number_amazon_search_results'] = np.sum((df.str.contains('https://www.amazon'))&(df.str.contains('k=')))

return df

#Apply the function

data = data.apply(number_amazon_results, axis = 1)

data['Number_amazon_search_results'].value_counts().sort_index()

Amazon’s market share per position

#List we will use to gather our data

out = [['Position', 'Amazon']]

#Loop columns and retrieve rounded percentage of Amazon's market share per position

for i in range(1,11):

s = data['Links {}'.format(i)]

out.append([i,round(((s.str.contains('https://www.amazon').sum()*100)/len(s)))])

#Transform the list of lists in a DataFrame

out = pd.DataFrame(data=out[1:],columns=out[0])

#Plot it

out.plot(kind='bar',x='Position',y='%',figsize=(8,8))

Amazon & affiliates’ market share per position

#See above

out2 = [['Position', 'Affiliates']]

#See above

for i in range(1,11):

s = data['Links {}'.format(i)]

out2.append([i,round(((s.isin(outlinks['Source'].unique()).sum()*100)/len(s)))])

#See above

out2 = pd.DataFrame(data=out2[1:],columns=out2[0])

#Pivot with the previous data

merge = out.merge(out2, on='Position')

#Set index

merge = merge.set_index('Position')

#Plot it

merge.plot(kind='bar',stacked=True, figsize=(7,7))

I think I covered everything. I hope this bit of transparency will help you understand better how the analysis was performed.